I’ve been working in IT for fourteen years and developing software for eleven.

My first development job was in a startup working alone and crashing for a deadline. Classic code and fix. I was pretty successful at it. I generally delivered on time. Often through sheer force of will. My big weakness was not reaching out to learn from other developers. A sure sign of a new or just bad self-taught coder is that they bang away at a problem like no one has ever solved it before. I’m embarrassed by some of the old code that has my name on it. Luckily, I wasn’t a cobol developer so all that work is long since trashed.

As I moved on to larger companies, I suffered under well-intentioned but corrosive attempts at waterfall. Craig Larman’s Agile & Iterative Development has a great description of how these attempts at perfectable planning and design are based on a misinterpretation of W.W. Royce’s writings.

Some of these projects were successful but the process prized simple agreement over trust. At it’s worst it created false hierarchies which hid incompetence and fetishized heroics. I was burning out. My friends were quitting. As if that wasn’t bad enough, even our success often fit Mike Cohn’s description of delivering the wrong software on time and on budget.

Meaningful products can emerge from horrible process. But a way of working that tears down talented people’s desire to work is tragic. To repeatedly participate in this is to sap the world of it’s limited supply inspiration, creativity and joy. This is evil. Now that I have authority, my main goal is to avoid this evil.

About seven years ago, I took my first training from Stephen McConnell’s Construx. Stephen McConnell inspires me. He is open to different practices, sets high standards for performance, and champions a code of ethics for our profession.

Over time I learned some techniques for effective iterative planning, risk management, and estimation. I learned how to work with others to deliver quality software. Through Earned Value Planning, regular inspection points and risk lists we built transparency into our practices. With realistic schedules we were able to maintain a reasonable work-life balance.

Still, the weakness I saw in my team and in my leadership style was relying way to heavily on the abilities and day to day motivation of individuals. I had to manage the project. My best developer had to work on it. If one of us had a bad day the project might grind to a halt. Our whole wasn’t adding up to the talents of the individuals.

It took me a while to really grok that excellence isn’t about adopting a shared set of practices. It’s about rallying around a shared set of values. I shifted from mentoring my team on how I did things to a conversation about why we do what we do.

We all want to make a contribution, we want to deliver business value for our employer, we want to be proud of our work, we want to learn, we want to be honest, we want time for our family’s, friends and outside interests.

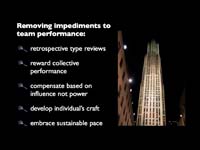

Over the last four years, we have adopted coding practices and a management style that supported our values. Specifically, Extreme Programming (XP) and Scrum. My recent focus has been on the management side. My short list of thought leaders is Alistair Cockburn, Mike Cohn, Ken Schwaber, and Jeff Sutherland.