A second iteration of my 6 min. pecha kucha on why I believe Agile practice makes me a better, more joyful person. Presented at Agile Day 2011 for AgileNYC.

1

1In pursuing agile practice I follow a family tradition of care and craft.

My mother is an immigrant. College educated but she made her living crafting the valences on fine drapery and upholstering furniture. She took pride in matching a pattern at the seams no matter how intricate. Her hands are wrecked from handling heavy fabric. Now she paints.

2

2My father is a retired engineer who hobbies with an engineer’s precision — calculating how much steel to mill from the inside of a casting reel or the optimal temperature to anneal tempered fly hooks.

There comes a point where people offer to pay him for his hobbies. He moves onto something else. He does these things for pleasure.

3

3My tween-age daughter aspires to be an engineer or scientist. She’s been on a Lego FIRST Robotics team since she was seven.

Her coaches wrote about her:

“You were chosen based on your ability to cooperate with others, problem solve, your endurance, care for the pieces, and enthusiasm for the task at hand.”

4

4My girl is a born agilist…

Ten years ago, Agile was a word chosen to rally a community.

Now it’s a brand promoted as a tool that solves problems when it’s more essentially a set of values that encourage us confront problems.

We value…

5

5

- Collaboration over negotiation

- Working software over specification

- People over process

- Responding to change over following a plan

Let me tell you about my early experiences with specifications and plans…

6

6Important people who don’t know how to build software but earn much more than software developers think big thoughts.

They call in other people who also don’t know how to build software but earn much less than software developers to shatter those big thoughts into a myriad small, literal and strangely ambiguous fragments.

7

7Then we plan…

Humans adore plans… we worship plans…

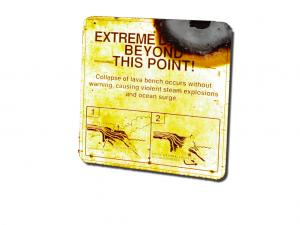

A driver put her faith in her GPS. It told her to turn onto a bridge. Problem was the bridge had been washed away. Her $160,000 Mercedes was swept away and she had to be rescued as it sank.

8

8The truth is people are inherently flawed. People are irreducibly complex. So is the software that solves their interesting problems. So while big ideas are great. Attempts to specify are great. Attempts to plan are great.

They’re just a conversation. They are not in and of themselves valuable.

9

9I want to engage with people to navigate the imperfect world we see in front of us

Focus on what I did, what I’m doing and what I want to do next. To arrive at a desired outcome together and to continually improve how we work and relate to each other.

Because reality is serendipity and opportunity…

10

10But it’s also setbacks, disappointments, and failure.

Failure isn’t any less awful when we refuse to see it. Worse is for failure to become, “the way things work around here”.

I accept failure. If we call it out, applaud the attempt and make changes so that we don’t repeat that exact failure again.

11

11This openness to risk results in an iterative, reflective way of working I love because I dearly want to spend each day doing a little less crap and a little more not crap than the day before.

I want to achieve this by reducing the net crap in the world, not simply delegating my crap to others.

12

12People…

There’s a Gallup study that claims the best and worst teachers, nurses, and policemen have more in common with each other than those in the broad middle. While the best are energized by their caring and use that passion to drive to the best outcomes, the worst are burnt and ruined by it.

The indifferent middle, they just crank along.

13

13A practice that puts process over people constrains behavior to avoid failure without consideration for the individual. In a concern for consistency it prevents the best even as it attempts to avoid the worst.

The agile community is not immune. We’re so focused on scale and process recipes, artifacts and tools.

14

14As if people are tangential. Easier to master than the software we engage with them to create.

Agile adoption in these terms becomes a mechanism for iterative mediocrity — a safe place for the indifferent middle.

I reject this.

Improving the workplace, improving worker satisfaction, improving collaboration is not a side affect of my agile practice. It is my practice.

15

15I acknowledge that successful products can emerge from horrible workplace. And that that good workplaces can create failed products.

But a way of working that tears down talented people’s desire to build is tragic. It saps the world of its limited supply inspiration, creativity and joy. This is evil.

16

16To combat this evil, my understanding of Agile principles requires honesty and trust among co-workers. A shared ambition to do better and be better while causing each other less unnecessary pain.

I focus on this in retrospectives, in one on ones, in coaching and in reflecting on my own decisions and actions.

17

17The great thing about even striving after this goal is as you work towards it your co-workers will give you permission to demand more of them.

…just as they will demand more of you.

This demand gives you an angel on your shoulder. It inspires even as it shames you into action.

18

18This isn’t easy. It is mortifying to confront your own limitations and the limitations of others.

But the action isn’t to change who you are. It is to adjust specific behaviors one at a time in the larger interests of the people you work with and the work you do together.

19

19The reward is that you get to be the same person with your boss that you are with your co-workers that you are with your staff. A person you can wear home. A wiser, better person than you were last month or last year.

This is a path my mother and father lay down for me and one I wish for my daughter.

20

20I don’t merely want success on a project or a job. I want to spend my life loving what I do. I want to be proud of my accomplishments,

…And I want to be proud of who I was as I attained them.

This is the existential joy I get from Agile practice.

Thank you.

This topic was inspired by Samuel Florman’s book, The Existential Pleasures of Engineering

Agile values call for honesty and trust. A shared ambition to do better and be better while causing each other less unnecessary pain.

Agile values call for honesty and trust. A shared ambition to do better and be better while causing each other less unnecessary pain.

This demand gives you an angel on your shoulder. Watching you as you work. It inspires even as it shames you into substantial actions that go against your nature. And you do this because your team needs you to.

This demand gives you an angel on your shoulder. Watching you as you work. It inspires even as it shames you into substantial actions that go against your nature. And you do this because your team needs you to.

But the reward is that you get to be the same person with your boss that you are with your peers that you are with your staff.

But the reward is that you get to be the same person with your boss that you are with your peers that you are with your staff.

The oozy failure wrapped in the chocolatey success of agile is when we focus on process mechanics and lose sight of people.

The oozy failure wrapped in the chocolatey success of agile is when we focus on process mechanics and lose sight of people.

We preclude the best in an attempt to avoid the worst and ensure mediocrity.

We preclude the best in an attempt to avoid the worst and ensure mediocrity.

As agile becomes popular it becomes a buzzword. It gets promoted as a tool that solves problems when at its heart it is a set of values that encourage you to confront problems.

As agile becomes popular it becomes a buzzword. It gets promoted as a tool that solves problems when at its heart it is a set of values that encourage you to confront problems.

Where the customer doesn’t entirely know what will succeed… Where they aren’t entirely steeped in the technology…

Where the customer doesn’t entirely know what will succeed… Where they aren’t entirely steeped in the technology…

And process gates (“handoffs”) kill collaboration.

And process gates (“handoffs”) kill collaboration.

I want to live in our imperfect reality.

I want to live in our imperfect reality.

I accept failure if we call it out as we recognize it, applaud the attempt and make changes so that we don’t repeat that exact failure again.

I accept failure if we call it out as we recognize it, applaud the attempt and make changes so that we don’t repeat that exact failure again.

My mother is college educated but made her living through physical labor. She made valances on fancy drapery and upholstered fine furniture.

My mother is college educated but made her living through physical labor. She made valances on fancy drapery and upholstered fine furniture.

My father is a retired engineer.

My father is a retired engineer.